By Kio Amachree

I once lived in Colherne Court, on the Old Brompton Road in Kensington, London.

Directly below me lived Lady Diana Spencer, who would later become the Princess of Wales.

Directly above me lived a group of Jamaicans who would quietly give me one of the most important educations of my life.

London has a way of arranging those kinds of contradictions.

The Jamaicans upstairs were not just neighbours. They re-educated me about Jamaica, West Indian history, music, politics, and identity. They became family. What law school could not teach me, they did—without lectures, without pretence, just lived truth.

One of them, Kirk, owned the flat upstairs. One night he threw a party and invited me. I arrived late. I had already been drinking with English friends at a pub, and by the time I made it upstairs I was flying—young, confident, careless, enjoying my London years far too much.

I walked into the party loud and unfocused.

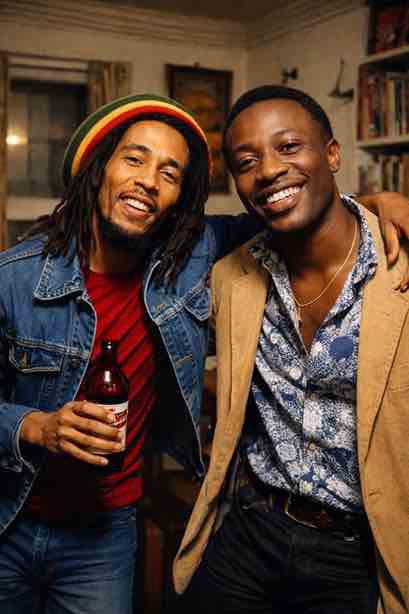

The first person I noticed was a short, light-skinned man standing alone against a wall. His dreadlocks were hidden under a Rasta cap. He was quietly sipping a bottle of Red Stripe, staring into space, detached from the noise and movement around him.

Drunk and rude, I walked up to him and asked him to get me a drink.

He did.

He returned with the bottle, smiling, calm, no attitude. At that moment Kirk rushed over from the dance floor and asked,

“Kio, have you introduced yourself to Bob?”

I looked at him, puzzled.

“Bob who?”

He pointed.

“Bob Marley. Bob, this is Kio, the Nigerian I keep telling you about.”

My head cleared instantly.

I knew that face. Of course I did. I was mortified. I had just treated Bob Marley like a houseboy. He looked smaller than he did on television. His dreads were hidden. That was why I hadn’t recognised him.

He laughed, brushed it off, and said,

“The famous Kio. I’ve heard a lot about you.”

From that moment, he took me under his wing.

Bob listened to my music. He never pushed drugs on me. I made it clear I didn’t like ganja, and he respected that completely. When a Jamaican girl once questioned why he was bothering with my “stupid music,” he exploded, asking her what she had done with her life except spread her legs. Bob did not suffer fools, especially lazy ones.

A few days later, I took Bob, his partner Cindy Breakspeare, and his entourage to Tramp, the London club where royalty, stars, and power mixed behind closed doors. Cindy, a former Miss World and the mother of Damian Marley, turned heads everywhere she went.

The staff refused to seat them without me present. Bob wouldn’t move without the member. When I arrived, we had a great night. Bob was completely down to earth. The fame only appeared when fans wouldn’t leave him alone—then he became Bob Marley the star. Otherwise, he was just a man, thoughtful, observant, amused by the madness around him.

Once, we sat in the home of a Jamaican gangster friend of mine named Trevor, a lovable rogue. Trevor owned a vicious cat—one of those animals that hates everyone except its owner. The cat took one look at Bob, jumped onto his lap, and began purring. The room went silent. Everyone knew that cat didn’t like anyone. Bob’s energy disarmed even animals.

One night, Trevor knocked on my door furious, asking where Bob was. He claimed Bob had been seeing his girlfriend. I told him bluntly that Bob and I talked about music, Africa, and politics—and to stop talking nonsense. When I told Bob later, he laughed and said Trevor could try his luck if he wanted.

Not long after, I flew to New York. I was at Island Records, meeting a friend in A&R. I casually mentioned that I had been spending time with Bob Marley.

The room went quiet.

They asked me how he looked. I said he looked strong, relaxed, in great form.

That’s when they told me the truth—Bob had terminal cancer. There was nothing they could do. And I was told not to tell anyone.

I left that meeting shaken.

London had placed a future Princess of Wales below me, the greatest reggae artist who ever lived above me, and a lesson I would never forget in between.

Greatness, I learned, does not announce itself. It doesn’t shout.

It stands quietly against the wall, sipping a beer, waiting to see who you really are.