“Asset seizure without stewardship is not justice; it is vandalism by the state, where wealth is taken in the name of the people, then quietly destroyed before it can ever serve them.” – Davies Blantyre.

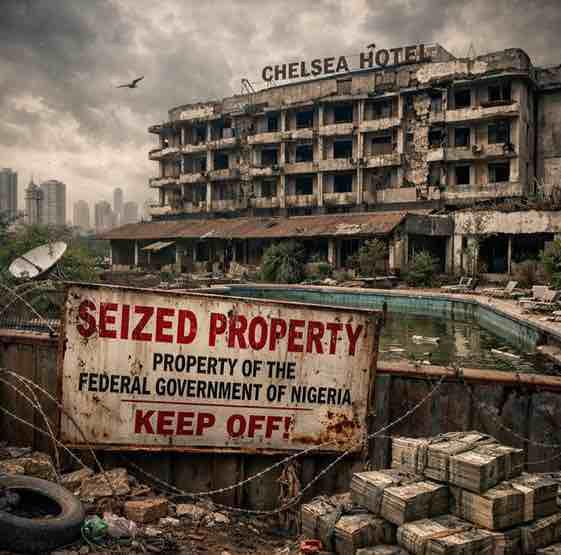

On 9th December 2005, Diepreye Alamieyeseigha was removed as governor of Bayelsa state of Nigeria. On 26 July 2007, he pleaded guilty before a Nigerian court to six charges and was sentenced to two years in prison. As part of his conviction, he forfeited several assets to the government of Nigeria. One of these assets was the Chelsea Hotel on Muhammed Buhari Way, Abuja.

What has unfolded with Chelsea Hotel and numerous other seized assets across Nigeria is not an unfortunate oversight or bureaucratic delay; it is a sustained failure of public stewardship that hollowly masquerades as anti-corruption enforcement.

When the EFCC seized Chelsea Hotel in 2007 from the former governor of Bayelsa State, the Nigerian state assumed more than physical custody of a building. It assumed fiduciary responsibility for a living enterprise, one that employed people, generated revenue, paid taxes, and contributed to the hospitality economy. Eighteen years later, that hotel lies in decay. Its infrastructure is ruined, its commercial value extinguished, its workforce dispersed. What was once a going concern has been allowed to rot into irrelevance. This is not asset recovery; it is asset annihilation.

The purpose of seizing assets linked to corruption is neither symbolic nor punitive theatre. It is to prevent the enjoyment of illicit wealth, preserve value pending judicial determination, and, where forfeiture is confirmed, return that value to the Nigerian people. None of these objectives is served when productive assets are locked up, abandoned, and left to deteriorate. On the contrary, such neglect actively subverts the logic of justice and inflicts a quiet but profound economic harm on the public.

Hotels, factories, farms, airlines, and logistics businesses are not inert objects. Their value depends on continuous operation, maintenance, skilled labour, regulatory compliance, and market relevance. The moment the state seizes such assets without a clear framework for interim commercial management, it begins to destroy what it claims to be safeguarding. Years later, what remains is often a shell; vandalised facilities, obsolete systems, unpaid creditors, and a balance sheet stripped of meaning.

The Chelsea Hotel is merely the most emblematic case. The recent seizure of assets linked to a former Attorney-General of the Federation, Abubakar Malami, raises the same question Nigeria has failed to answer for nearly two decades; will these properties be preserved as productive public assets, or will they be quietly sacrificed to bureaucratic inertia while legal processes crawl on indefinitely?

The routine invocation of “ongoing court proceedings” is an excuse, not an explanation. Courts do not require assets to be abandoned for justice to run its course. In fact, in serious jurisdictions, the opposite principle prevails, seized assets are professionally managed as going concerns, revenues are held in escrow, accounts are audited, and value is preserved pending final judgment. If forfeiture is upheld, the state inherits a viable enterprise. If it is not, the owner is entitled to an asset that still exists, not a ruin created by state neglect.

Nigeria’s refusal to institutionalise this practice reveals a deeper governance pathology. Seizures are treated as endpoints rather than beginnings, press statements rather than processes. Asset decay becomes normalised, and with it arise darker suspicions; that abandonment enables quiet asset stripping, undervalued disposals, or eventual re-capture by politically connected interests once public attention fades.

At the centre of this failure sits a particularly glaring contradiction. the systematic sidelining of the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON).

AMCON was created precisely to handle distressed, encumbered, or strategically sensitive assets. Its statutory purpose is to stabilise value, manage complex commercial holdings, and recover economic worth for the public good. It possesses operational experience across banking, aviation, real estate, hospitality, and industrial enterprises. If Nigeria had any intention of preserving the value of seized hotels and businesses, AMCON should have been the default institutional custodian.

Instead, seized assets are left in the hands of law enforcement agencies whose mandate and expertise lie in investigation and prosecution, not enterprise management. The EFCC and similar bodies are not hotel operators, property managers, or turnaround specialists. Expecting them to preserve commercial value is not merely unrealistic, it is reckless. This institutional mismatch lies at the heart of the decay.

The irony is difficult to ignore. AMCON has successfully taken over and operated airlines, power assets, and large real estate portfolios under conditions far more complex than those surrounding many seized corruption-linked properties. If AMCON can intervene to stabilise failing private enterprises in the interest of systemic financial stability, what justification exists for allowing seized, fully functional businesses to disintegrate under state custody?

This is not a legal problem. There is no prohibition against interim commercial management of seized assets. It is a failure of political will, administrative coordination, and governance discipline. By refusing to integrate AMCON into the asset recovery pipeline, the Nigerian state undermines its own anti-corruption narrative and sabotages its economic interests.

The consequences are concrete. Each abandoned asset represents lost tax revenue, lost employment, degraded urban infrastructure, and diminished investor confidence. What serious investor will trust assurances about property rights and regulatory competence when the state itself cannot manage assets it has lawfully seized? Anti-corruption that destroys economic value is not reform; it is self-harm.

There is also a moral failure at play. Nigerians are told that seized assets are “recovered for the people.” Yet the people derive no benefit from abandoned hotels, idle factories, or vandalised estates. Justice delayed is corrosive; justice that impoverishes the public while waiting is indefensible.

The solution is neither radical nor obscure. Nigeria must formally integrate AMCON into the seizure and recovery framework, mandating it to assume custody of going concerns immediately after seizure, operate them transparently, preserve jobs and standards, ring-fence revenues, and publish audited accounts. Anything less is an abdication of responsibility.

Until this is done, every decaying seized asset, from Chelsea Hotel to the most recent high-profile forfeiture, will stand as an indictment of the authorities. Not for failing to seize property, but for failing to understand stewardship. The real scandal is not that corrupt officials once owned these assets, it is that the Nigerian state, having taken them, has proven incapable of doing better.

Dr. EK Gwuru is a writer, social analyst, and creative strategist based in Nkolo Ikembe. He explores the intersections of culture, governance, and human progress across Africa and the diaspora.