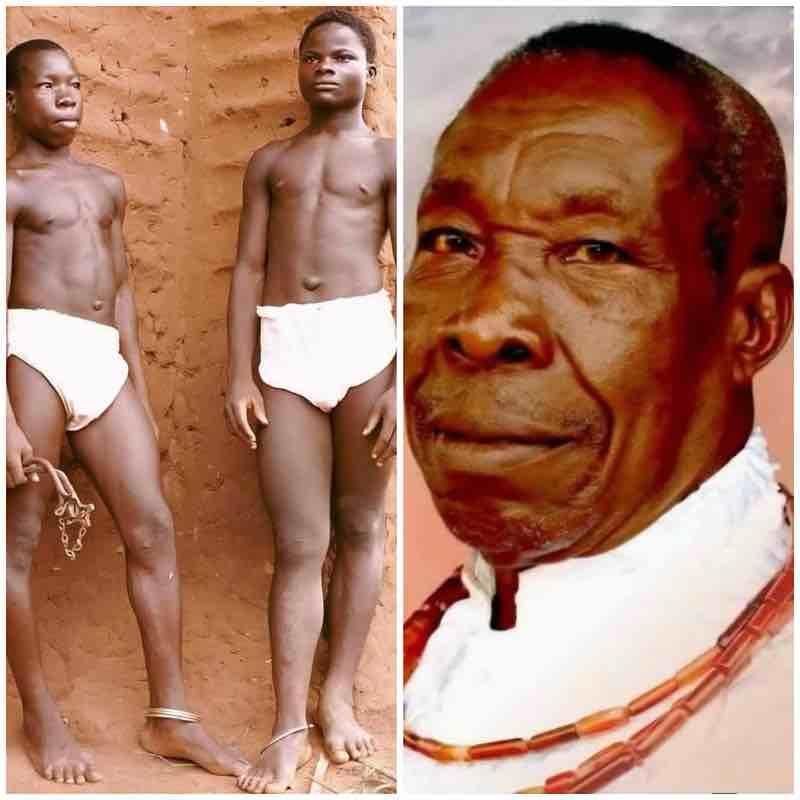

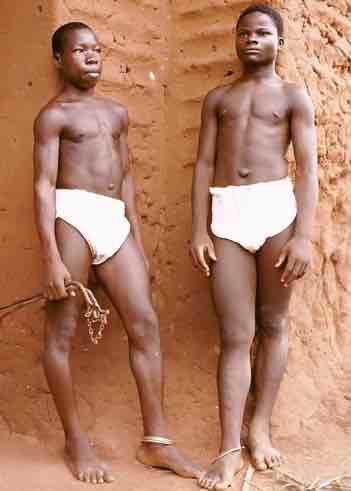

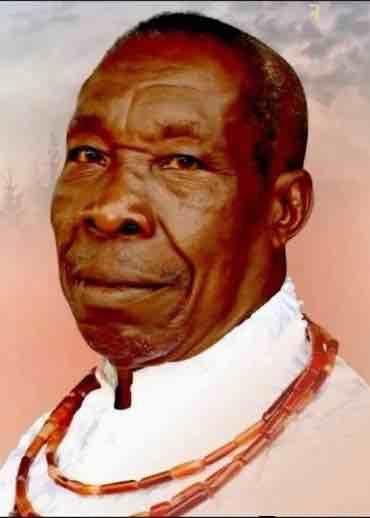

These two images tell one continuous Benin story across time. The first photograph, taken in 1959 by Eliot Elisofon during his Life Magazine assignment, shows two teenage Omuada in the royal court of Oba Akenzua II. At left is Isaac Osazuwa, aged 17, holding the keys to the palace courtyard and wearing three anklets that marked his rank. At right stands Robinson Eguagie, aged 16, with a single anklet. The second image shows Isaac Osazuwa decades later—no longer a palace youth, but a titled Benin chief. Together, they quietly but powerfully explain what the institution of Omuada truly represents.

In the Kingdom of Benin, an Omuada (plural: Umuada or Emuada) is a state sword bearer and royal attendant, entrusted with carrying the Ada and Eben—the sacred swords that symbolize the Oba’s authority, justice, and historical continuity. This was not casual service. These young men lived at the heart of palace life, observing rituals, learning protocol, and absorbing the discipline of governance and statecraft from an early age.

From time to time, older photographs, (those taken before 1897 or from the reign of Oba Eweka II after 1914), raise questions—especially around dress. In earlier periods of Benin history, palace attendants were sometimes minimally clothed or bare. This was not humiliation or servitude. In Benin culture, such presentation symbolized youth, ritual purity, and complete devotion to royal service. Beginning from the reign of Oba Akenzua II (1933-78), whose era coincided with the Oba’s participation in government, stricter colonial scrutiny, photography, and a changing public gaze, outward presentation evolved. And by the start of the reign of Oba Erediauwa in 1979, simple garments replaced earlier forms, but the role, meaning, and status of the Omuada remained exactly the same. What changed was appearance, not purpose.

Crucially, Omuada were not slaves or servants. They were wards of the palace—often drawn from notable families of allied or vassal communities—and their service formed part of a broader political and cultural bond with the Oba. The anklets seen in the photograph were not shackles; they were symbols of hierarchy and responsibility. Holding the keys to the palace courtyard was a mark of trust.

Service as an Omuada was widely regarded as a training ground for leadership. History records that several former Omuada went on to build successful careers in business, music and several other endeavors with some of them becoming rulers in their own domains, including the Deji of Akure and the Olowo of Owo. Within Benin itself, diligent service could—and often did—lead to elevation into the chieftaincy. Isaac Osazuwa’s life reflects this journey clearly: from sword bearer in his youth to titled chief in maturity.

Today, the institution of Omuada still exists within Benin’s traditional structure. These images remind us that Benin palace institutions were deliberate, hierarchical, and purposeful—designed to raise leaders, not create servants; to instill discipline, not bondage.

In Benin history, service was often the path to honor—and the Omuada tradition is one of the clearest examples of that truth.

Credit: Jefferson Uwoghiren.